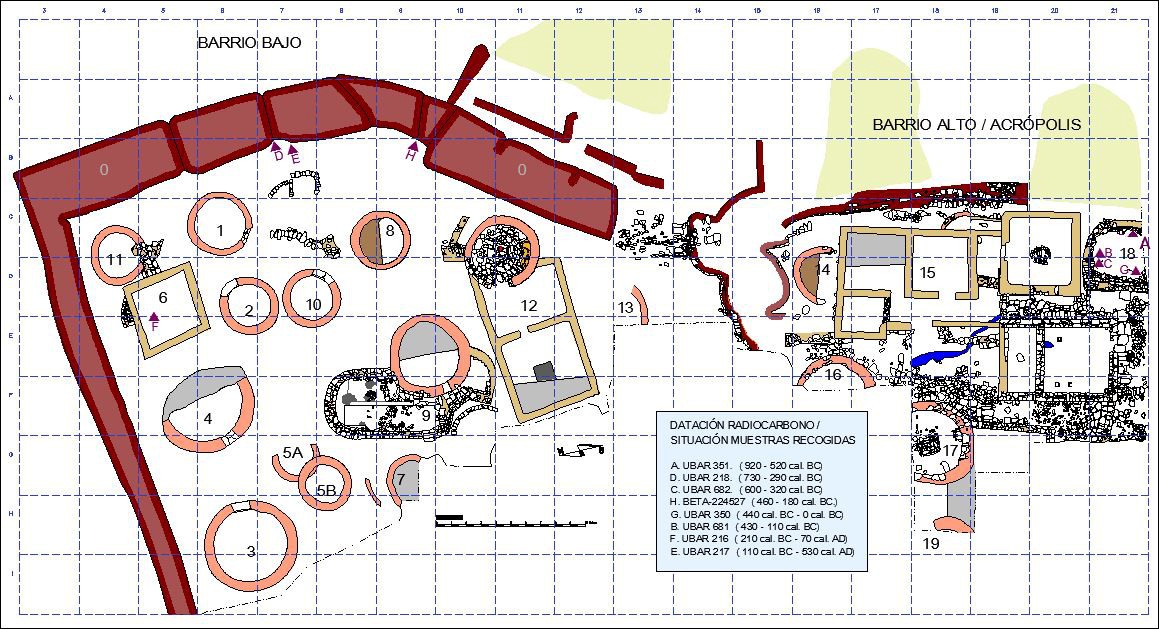

Ya en el año 1984, el profesor Jordá Cerdá se pronunciaba a favor de la existencia en San Chuis de una ocupación prerromana que sería la responsable de la fundación y del desarrollo urbano del poblado (Jordá Cerdá 1984, 1985). A fin de conseguir una secuencia cronoestratigráfica basada en dataciones radiocarbónicas que permitiera acreditar esta hipótesis, se procedió a la toma de una serie de muestras que serían enviadas para su datación. Así, en 1990, 1992 y 2001, se enviaron al Laboratori de Datació per Radiocarboni de la Universitat de Barcelona (UBAR) bajo la supervisión de Joan S. Mestres Torres, tres lotes

de muestras de diferentes contextos estratigráficos y arqueológicos, recuperadas durante las excavaciones del profesor Jordá Cerdá (1979-1986) y en una campaña de campo posterior realizada por J. F. Jordá Pardo y Mercedes García Martínez (2001). Todas las muestras procedían de contextos arqueológicos y estratigráficos perfectamente identificados.

En 1990 se envía por lo tanto el primer lote de muestras recogidas, que constaba de tres ejemplares, y que formaban parte de una secuencia estratigráfica clara cuya datación fue financiada por el Instituto Tecnológico Geominero de España dentro del Programa Básico de I+D en Geología Ambiental (1989-1992). La obtención de una fecha bastante antigua para la más inferior de las tres muestras de este primer lote, supuso una gran novedad en el panorama de los castros asturianos. Este hecho obligó, siguiendo los dictados del método científico, a datar en 1992 dos nuevas muestras de los materiales antiguos que verificaron las ya obtenidas. Los resultados de ambas campañas de datación fueron publicados, junto con otras dataciones de castros asturianos, en el trabajo “Radiocarbono y cronología de los castros asturianos” (Cuesta Toribio et al. 1996). Las críticas recibidas desde algunos sectores de la Arqueología asturiana (Camino Mayor 2000: 10, 12; Ríos González y García de Castro Valdés 2001: 95-97) obligaron a verificar empíricamente los resultados obtenidos, por lo que en 2001 se tomaron nuevas muestras que fueron enviadas a UBAR para su datación, obteniendo dos nuevas fechas que vinieron a ratificar las anteriores (Jordá Pardo, Mestres Torres y García Martínez 2002).

Finalmente, durante el estudio de los materiales metálicos llevados a cabo por Carlos Marín Suárez, se descubrió un carbón englobado en una escoria férrica, que se dató en Beta Analytic Inc. (Miami, Florida, EE.UU.) obteniendo una nueva fecha concordante de nuevo con las anteriores (Marín Suárez, Jordá Pardo y García-Guinea 2008: 56-59).

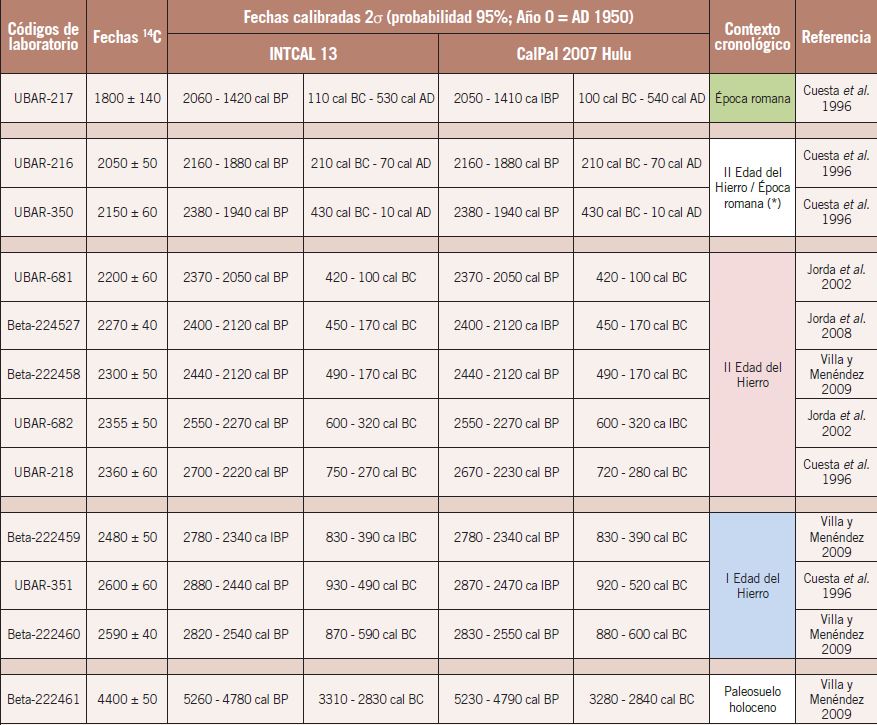

Por tanto, en este momento existen ocho fechas radiocarbónicas que configuran una amplia secuencia que comprende desde la Primera Edad del Hierro hasta el final de la ocupación romana del castro (Jordá Pardo 2009; Jordá Pardo et al. 2009; Jordá Pardo, Marín Suárez y García-Guinea 2011) (Figura 1).

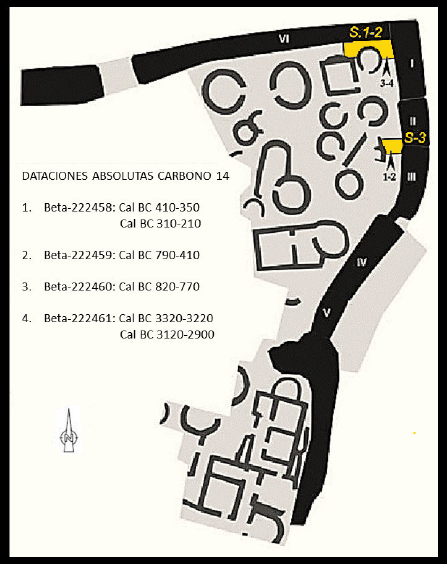

Figura 1. Plano de san Chuis donde se recogen los puntos de obtención de las muestras radiocarbónicas y su cronología. De Jordá Pardo 2009: 53 fig. 2, modificado. | Plan of San Chuis where the points from which radiocarbon samples were obtained and their chronology are shown. From Jordá Pardo 2009: 53 fig. 2, modified.

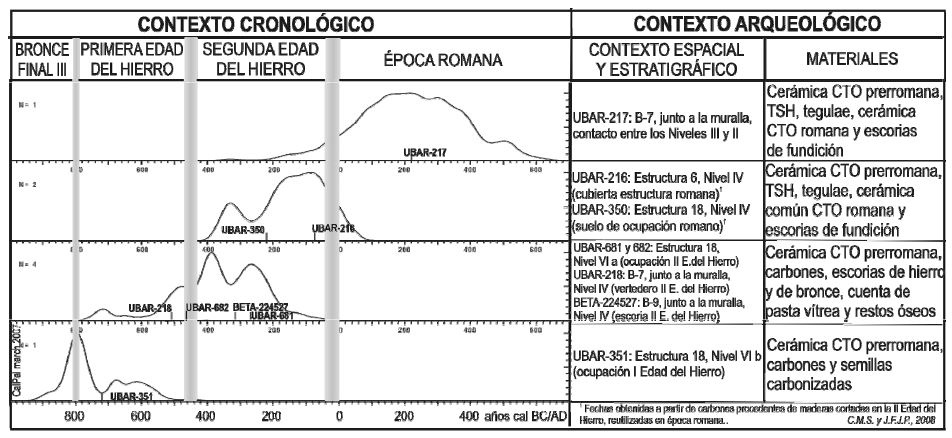

Figura 1. Plano de san Chuis donde se recogen los puntos de obtención de las muestras radiocarbónicas y su cronología. De Jordá Pardo 2009: 53 fig. 2, modificado. | Plan of San Chuis where the points from which radiocarbon samples were obtained and their chronology are shown. From Jordá Pardo 2009: 53 fig. 2, modified.Para realizar el análisis cronológico, se calibraron las fechas radiocarbónicas a 2 sigma (95 % de probabilidad) mediante la curva de calibración CalPal 2007 Hulu, incluida en el programa CalPal (Version March 2007) (Weninger, Jöris y Danzeglocke 2007). Los resultados de la calibración se presentan en las Figuras 2 Y 3. En la Figura 2 se muestran las curvas de probabilidad acumulada obtenidas a partir de la calibración de las fechas radiocarbónicas agrupadas por su posición cronoestratigráfica, indicando su contexto espacial y estratigráfico y los materiales asociados. En la Figura 3 se muestran las fechas radiocarbónicas calibradas.

Figura 2. Curvas de probabilidad acumulada obtenidas a partir de la calibración dendrocronológica de las dataciones radiocarbónicas agrupadas por su posición cronoestratigráfica, indicando su contexto espacial, estratigráfico y los materiales asociados De Marín Suárez, Jordá Pardo y García-Guinea 2008: figura 3 | Cumulative probability curves obtained from the dendrochronological calibration of radiocarbon dates grouped by their chronostratigraphic position, indicating their spatial and stratigraphic context and associated materials From Marín Suárez, Jordá Pardo and García-Guinea 2008: figure 3.

Figura 2. Curvas de probabilidad acumulada obtenidas a partir de la calibración dendrocronológica de las dataciones radiocarbónicas agrupadas por su posición cronoestratigráfica, indicando su contexto espacial, estratigráfico y los materiales asociados De Marín Suárez, Jordá Pardo y García-Guinea 2008: figura 3 | Cumulative probability curves obtained from the dendrochronological calibration of radiocarbon dates grouped by their chronostratigraphic position, indicating their spatial and stratigraphic context and associated materials From Marín Suárez, Jordá Pardo and García-Guinea 2008: figure 3.PERIODOS DE OCUPACIÓN

El periodo de ocupación más antiguo del castro corresponde a la fecha UBAR-351 (A) 2.600 ± 60 BP, cuya calibración con la máxima probabilidad (95 %) ofrece la horquilla 920 – 520 cal. BC (Figura 107). Esta fecha fue obtenida de una muestra del nivel basal (Nivel VI b o UE-94) de la secuencia estratigráfica del interior de una estructura circular antigua del barrio alto ( Estructura 18, cuadrícula C-21).

Este nivel rellenaba la paleotopografía del fondo de la estructura y se apoyaba directamente sobre la alteración de la roca del sustrato. La muestra procede de un depósito de semillas ubicado en la base del nivel dentro de un pequeño agujero limitado por la roca del sustrato y lajas de pizarra, situado a una cota

aproximada de 778,50 m, unos 55 cm por debajo del arranque de los muros de la estructura circular superpuesta, según consta en las plantas levantadas durante la excavación. Este nivel está asociado a varios agujeros de poste de una posible estructura vegetal, que estratigráficamente se encuentra por debajo

de los cimientos de la estructura pétrea circular citada y está afectado parcialmente por los vaciados romanos ligados a una estructura rectangular superpuesta. De él proceden cerámicas prerromanas de la Primera Edad del Hierro. Tanto la estratigrafía como la superposición de estructuras, nos permiten pensar que el nivel basal muestreado corresponde a una etapa de ocupación indígena del poblado claramente anterior a la remodelación generalizada del yacimiento de la Segunda Edad del Hierro. La muestra datada

corresponde a las semillas aparecidas en dicho nivel basal siendo un elemento muy válido a la hora de datar el nivel que las contiene, existiendo un margen temporal mínimo entre los tres procesos implicados en su génesis: recolección, almacenamiento y combustión.

El siguiente periodo de ocupación del castro se encuentra identificado por cinco fechas radiocarbónicas: UBAR-218 (D), BETA-224527 (H), UBAR-682 (C), UBAR-681 (B), UBAR-350 (G) y UBAR-216 (F). Las cuatro primeras cumplen perfectamente los requisitos de representatividad (asociación y sincronía) de las

muestras (Mestres Torres, 2003), mientras que las dos últimas cumplen los requisitos de asociación, pero carecen de sincronía, dado que la formación del material datado es anterior al acontecimiento arqueológico al que se encuentra asociado. Por ello, en la figura 106 se presentan los dos grupos de fechas de forma separada.

La fecha UBAR-218 (D) 2.360 ± 60 BP (730 –290 cal. BC), corresponde a una muestra de carbones selectos y tierra carbonosa con restos de carbón que procede del nivel basal dispuesto sobre la alteración del sustrato pizarroso en las proximidades de la muralla de módulos del Barrio bajo, dentro del cuadro B-7 (campaña de 1985). Se trata del Nivel IV (UE-99), arcilloso por la descomposición de la roca madre, rico en materia orgánica carbonizada, con restos de fauna doméstica (vaca, cerdo-jabalí). Esta zona del barrio bajo

(cuadrículas B-7, B-8, B-9, C-7 y C-8) corresponde a un espacio ubicado entre el caserío y las defensas, aparentemente vacío, con pequeñas estructuras pétreas lineales ligeramente curvadas, que apoyan directamente sobre el nivel basal de roca descompuesta, a las que se superponía una especie de camino

enlosado, presumiblemente ya de época romana pues también cubre estructuras circulares próximas amortizadas en dicha época. El Nivel IV (UE-99), interpretado como un basurero e infrayacente a un nivel de ocupación romano (UE-97), apoya sobre la cara interna de la muralla de módulos, de ahí que la fecha UBAR 218 se haya utilizado como terminus post quem para la construcción de la muralla (Cuesta Toribio, Maya González, Mestres i Torres, & Jordá Pardo, 1996, págs. 231-232). Este Nivel IV contiene exclusivamente cerámicas prerromanas, lo que está en sintonía con la fecha radiocarbónica que lo data y con la aparición de una cuenta oculada en este nivel (Marín Suárez, 2007), que precisamente suelen datarse en fechas que se solapan con UBAR 218 (siglos IV-II a. C.). Por encima se encuentra un nivel romano (Nivel III/UE-98) que

presenta numerosos fragmentos de TSH y tégula en relación con una gran cantidad de fragmentos de cerámica prerromana.

De esta misma zona del barrio bajo del castro se obtuvo, en 2007, una nueva fecha para el techo del Nivel IV. Se trata de BETA-224527 (H) 2.270 ± 40 BP (460 – 180 cal. BC), obtenida a partir de una muestra de carbón englobada en el interior de una escoria férrica procedente del contacto entre el Nivel IV (UE-103)

con el Nivel III (UE-102), en el cuadro B-9 (campaña de 1985) (Marín Suárez, Jordá Pardo y García-Guinea 2008; Jordá Pardo, Marín Suárez y García-Guinea 2011). Este nivel se caracteriza por la presencia de numerosas escorias y de multitud de cerámicas, incluyendo algunos fragmentos de TSH, sobrepasadas

por la acción de altas temperaturas en estas cuadrículas. Todo ello, junto a las pequeñas estructuras en arco antes descritas, interpretables como paravientos, podría ser indicativo de labores metalúrgicas en esta zona, desde época prerromana y puede que continuadas en época romana. Es bastante probable que las remociones de terreno, fruto de dichos trabajos metalúrgicos, hayan alterado los estratos, mezclando materiales, causa por la que no encontraríamos en B-9 ningún nivel exclusivamente con cerámicas prerromanas. No obstante, en todas estas cuadrículas, tanto en los niveles exclusivamente prerromanos, como en los romanos, hay una amplia representación de cerámicas prerromanas. El interés de esta fecha radica en que por primera vez se data de manera directa el proceso de elaboración del hierro en momentos anteriores a la ocupación romana en los castros asturianos. Esta zona ha sido considerada como zona de trabajo o «zona artesanal».

Las muestras de las que se obtuvieron las fechas UBAR 682 (C) 2.355 ± 50 BP (600 – 320 cal. BC) y UBAR 681 (B) 2.200 ± 60 BP (430 – 110 cal. BC) fueron extraídas en una campaña específica en el año 2001 y proceden de los sedimentos carbonosos adosados a la cara interna de los cimientos del muro circular, situados entre las cotas 779,10 y 779,05 m, entre 30 y 25 cm por debajo del suelo de ocupación romano de la estructura 18 (cuadrícula C-21) del barrio alto (Jordá Pardo, Mestres Torres, & García Martínez, 2002). A la vista de los

datos disponibles (Marín Suárez & Jordá Pardo, 2007), las muestras datadas corresponden al tramo superior del Nivel VI del interior de esta estructura o Nivel VI a (UE-93), correlativo a la petrificación de la estructura 18, y afectado en mayor medida por los vaciados de época romana por lo que sólo se documenta pegado a los muros circulares sin que haya quedado constancia del mismo en el interior de la citada estructura. Entre los escasos restos de este nivel no se han recuperado cerámicas, si bien su atribución a la Segunda Edad del Hierro parece clara tanto por su posición estratigráfica como por las fechas radiocarbónicas que lo datan. A la vista de las fechas presentadas, el Nivel VI a del interior de una estructura circular del barrio alto es claramente correlacionable con el Nivel IV de la zona artesanal próxima a la muralla del barrio bajo.

En cuanto a las fechas que presentan problemas de asociación, la primera de ellas UBAR-350 (G) 2.150 ± 60 BP (440 cal. BC – 0 cal. AD), se obtuvo de un fragmento de carbón procedente del tercer nivel (Nivel IV, UE-89 y UE-90) de ocupación de la secuencia estratigráfica obtenida en la estructura 18 del barrio alto (cuadro C-21, campaña de 1983) que es correlativo a los muros longitudinales que remodelan la estructura circular anterior asociada a las fechas UBAR-682 y UBAR-681. Este Nivel IV, que se encuentra situado unos 25/30 cm

por encima del Nivel VI-b del que proceden UBAR-681 y UBAR-682, corresponde al suelo de ocupación romano de la estructura rectangular que descansa sobre la estructura circular antigua ya citada. Los materiales de este nivel corresponden a cerámicas prerromanas, Terra Sigillata Hispánica y cerámica común romanas, así como fragmentos de hierro, que lo sitúan en los primeros momentos de la ocupación romana del castro, en torno al siglo I d.C. (Manzano Hernández 1985). A primera vista, la edad obtenida para la muestra del nivel, con ocupación romana, no parece que se ajuste a la esperada, existiendo un desfase mínimo entre la datación cultural y la radiocarbónica de aproximadamente un siglo. Es posible que nos encontremos ante un fragmento de madera carbonizada durante el desarrollo del suelo de ocupación romano, madera que debió ser cortada en un momento concreto de la horquilla calibrada que ofrece la fecha por los habitantes prerromanos del castro y que pudo tener un uso como elemento de cubrición o sustentación en la estructura circular antigua, siendo retomada en época romana y sometida a combustión.

Con la fecha UBAR-216 (F) 2050 ± 50 BP (210 cal. BC – 70 cal. AD), ocurre algo similar. Procede de una muestra de tierra carbonosa con abundantes restos de carbón obtenida en un nivel de materia orgánica carbonizada (Nivel III, UE-77) que ocupa toda la extensión del interior de la única estructura cuadrangular

del vértice NE del barrio bajo (estructura 6, cuadrícula D-5, campaña 1984). Es una estructura cuadrangular de época romana, para cuya construcción fue necesaria la destrucción y arrasamiento de tres estructuras indígenas, encontrándose una bajo sus cimientos, rellenada por cascotes, y las otras dos en posición cercana. Un pavimento de losas de pizarra se dispone al pie de la estructura cuadrangular cubriendo los arranques de los muros de una circular. La edad radiocarbónica obtenida corresponde a la de los materiales vegetales

utilizados para la elaboración de la cubierta de la estructura cuadrangular en cuyo interior fueron recogidos. Dicha cubierta se levantó durante la ocupación romana, probablemente en sus inicios cuando se produce el arrasamiento de determinadas estructuras para la construcción de otras nuevas. Los materiales de la cubierta, a tenor de su edad calibrada pueden corresponder a restos de maderas reutilizadas por los romanos procedentes de las construcciones indígenas, o bien si nos atenemos a la fecha más reciente aportada por la calibración a dos sigmas podrían incluso corresponder a esos momentos iniciales de la ocupación romana. Estos materiales de la cubierta fueron posteriormente incendiados al abandonarse el poblado por sus ocupantes romanos, destruyéndose la estructura que los soportaba e inutilizándose esta

para los fines con que fue concebida.

Por último, el final de la ocupación romana del castro ha sido datado mediante la fecha UBAR-217 (E) 1.800 ± 140 BP (110 cal. BC – 530 cal. AD), correspondiente a una muestra de tierra carbonosa con trocitos de carbón que procede de las proximidades de la muralla en el barrio bajo (cuadrícula B-7, campaña de 1985). La muestra fue obtenida en la base de un delgado nivel (Nivel II) situado por encima del nivel general de derrumbe del poblado (Nivel III, UE-98), caracterizado por la presencia de cantos y bloques de pizarra englobados en una matriz arcilloso-arenosa, producto de la destrucción de la obra de mampostería de los muros de las estructuras. La muestra fue tomada en la secuencia que en la base contiene el Nivel IV fechado mediante UBAR-218 y estratigráficamente se encuentra por encima de UBAR-216. Los restos cerámicos que contiene el nivel muestreado corresponden a una ocupación tardía del poblado, centrada en el siglo II d.C. (Manzano Hernández 1985). Esta fecha representa la ocupación más tardía del castro documentada hasta el

momento, que tuvo lugar probablemente después de su destrucción parcial. Ello concuerda con el final de los castros del centro-occidente cantábrico que grosso modo podemos situar en el s. II d.C. y comienzos del s. III d.C.

INFORMACIÓN COMPLEMENTARIA

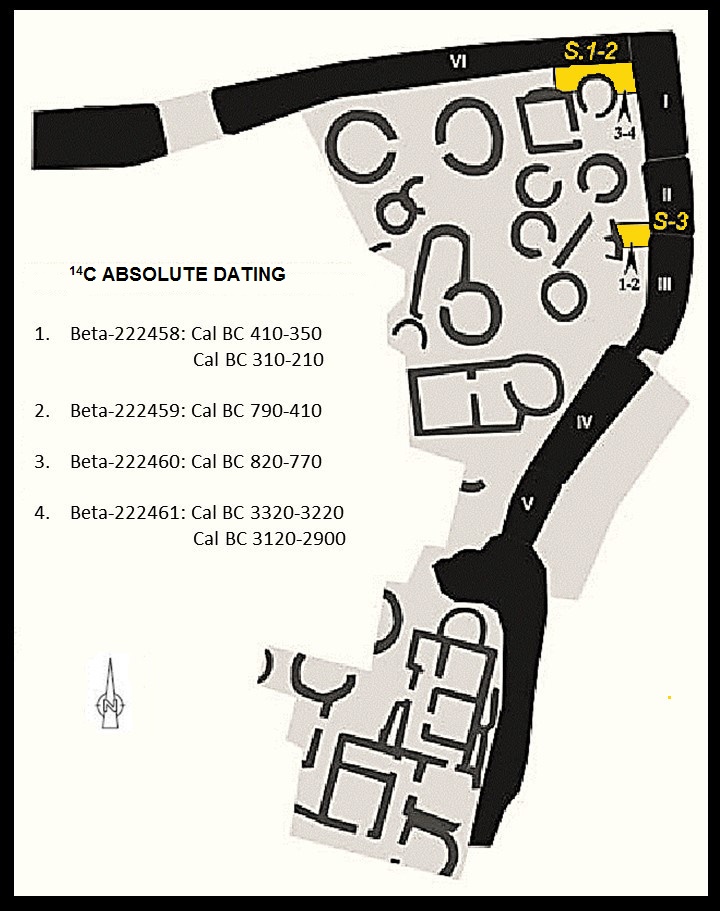

En el año 2006 y en el marco del Plan Arqueológico del Navia-Eo, Villa Valdés y Menéndez Granda acometen varios sondeos en la muralla del castro con el fin de conocer su estabilidad y su solidez y corregir las posibles patologías que favorecían el progreso de grietas, pérdida de aparejo y derrumbes (Villa Valdés

y Menéndez Granda 2009). Con el fin de confirmar la serie estratigráfica y dar cronología a las secuencias constructivas registradas en los sondeos, seleccionaron cuatro muestras orgánicas para proceder a la estimación de su edad mediante el radiocarbono (Figura 4).

La primera muestra (SC.01/06) se extrajo del horizonte sedimentario originado al pie de la muralla modular en el sondeo 3 y fue identificada por el laboratorio como Beta-222458. La fecha convencional que proporcionó fue de 2300 ± 50 BP, que una vez calibrada a 2 sigma facilitó una doble horquilla temporal

comprendida entre el 410-350 a.C. y el 310-210 a.C.

La segunda (SC.03/06), que también procedía del sondeo 3, fue recogida entre los sedimentos acumulados contra el paramento externo de la primitiva muralla. Su identificación de laboratorio es Beta-222459. Proporcionó una fecha convencional de 2480 ± 50 BP que calibrada a 2 sigma ofrece un intervalo de

confianza comprendido entre el 790-410 a.C.

La tercera muestra (SC.04/06) procede ya del sondeo 1 y, al igual que en el caso anterior, fue recogida entre los depósitos acumulados contra el paramento interno de la muralla más antigua, subyacente a la de estructura modular. Su identificación de laboratorio es Beta-222460. Proporcionó una fecha

convencional de 2590 ± 40 BP que calibrada a 2 sigma ofrece un intervalo de confianza comprendido entre el 820-770 a.C.

La cuarta y última muestra (SC.05/06) también procede del sondeo 1. Fue recogida en el paleosuelo sobre el cual se instalaría la primera de las murallas. Su identificación de laboratorio es Beta 222461. Proporcionó una fecha convencional de 4400 ± 50 BP que calibrada a 2 sigma ofrece una doble horquilla temporal comprendida entre el 3320-3220 a.C. y el 3120-2900 a.C. (Villa Valdés & Menéndez Granda, 2009, págs. 170-171).

La primera y última muestra han proporcionado fechas perfectamente coherentes con las obtenidas anteriormente en San Chuis y vienen a confirmar tres hechos fundamentales ya conocidos:

− Se puede considerar prácticamente probada la fundación del castro de San Chuis en las postrimerías de la Edad del Bronce, cuestión que ya se señaló tras el análisis de las primeras muestras y la interpretación

del contexto estratigráfico del castro.

− Durante la II Edad del Hierro, los asentamientos de fundación antigua experimentaron, como ya hemos señalado en capítulos anteriores, profundas transformaciones en su estructura urbana y defensiva. Las

murallas de módulos son una de las referencias esenciales en la percepción de ese cambio.

− El marco temporal en el que se verifica la implantación de las murallas modulares es esencialmente el Mismo en todos los castros del occidente asturiano. Entre el siglo IV y el siglo II a.C. se confirma su presencia en los castros de Chao Samartín, en el de Cabo Blanco, en El Franco, y en Monte Castrelo de Pelóu, en Grandas de Salime.

Figura 4. Distribución de los sondeos con indicación de la procedencia y resultado de su datación. De Villa Valdés y Menéndez Granda 2009: 166, Fig. 7, modificado.

Figura 4. Distribución de los sondeos con indicación de la procedencia y resultado de su datación. De Villa Valdés y Menéndez Granda 2009: 166, Fig. 7, modificado.Sin embargo, la segunda y tercera muestra (Beta-222459 y Beta-222460) sí que han proporcionado datos novedosos. La primera de ellas, Beta 222459, nos traslada a la fase I c, de transición con la Segunda Edad del Hierro, con fechas 790-410 a. C. Podría hacernos pensar que tras la fundación de un poblado fortificado en la fase I b y circunscrito principalmente al barrio alto pasaría a desarrollarse una ampliación del espacio construido en esta fase de transición, para acabar estabilizándose estas nuevas dimensiones a comienzos de la fase II con el levantamiento de la muralla de módulos. Sin embargo la segunda datación (Beta-222460 con fechas 820-770 a.C.) nos lleva a replantearnos esta cronología así como la evolución urbanística del castro, ya que, a tenor de su calibración, parece que esta muralla de lienzo continuo se levantó en el mismo

momento de la fundación del castro. Se puede sugerir entonces que esta esquina noreste del poblado o Barrio Bajo, pudo estar ocupada, al igual que el Barrio Alto, ya desde el primer momento de la fundación del mismo, en la fase I b, y que fue defendida con una muralla de lienzo continuo de 1,5 m de anchura. De esta fase de la Primera Edad del Hierro contamos entonces con la estructura de agujeros de poste del barrio alto y con estos tramos de muralla continua del Barrio Bajo (Jordá Pardo, Marín Suárez y Molina Salido 2014: 155).

Abajo puede verse una tabla resumen con todas las dataciones existentes para San Chuis y sus referencias bibliográficas (Figura 6):

Already in 1984, Professor Jordá Cerdá was in favour of the existence in San Chuis of a pre-Roman occupation that would be responsible for the foundation and urban development of the village (Jordá Cerdá 1984, 1985). In order to obtain a chronostratigraphic sequence based on radiocarbon dating that could allow us to prove this hypothesis, we proceeded to the collection of a series of samples that would be sent for its dating. Thus, in 1990, 1992 and 2001, three lots of samples from different stratigraphic and archaeological contexts recovered by Professor Jordá Cerdá during his excavations (1979-1986) and by J. F. Jordá Pardo and Mercedes García Martínez in a later campaign (2001) were sent to Laboratori de Datació per Radiocarboni of the Universitat of Barcelona (UBAR) under the supervision of Joan S. Mestres Torres. All samples came from perfectly identified archaeological and stratigraphic contexts. In 1990, therefore, the first batch of collected samples was sent, consisting of three specimens, which were part of a clear stratigraphic sequence whose dating was financed by the Instituto Tecnológico Geominero de España (Geo-Mining Technological Institute of Spain) within the Basic Program of R & D in Environmental Geology (1989-1992). The obtaining of a quite ancient date for the oldest one of the three samples of this first batch, supposed a great novelty in the panorama of the Asturian hillforts. This fact obliged, in accordance with the dictates of the scientific method, to date in 1992 two new samples of the old materials that could verify the already obtained ones. The results of both dating campaigns were published, along with other dates of Asturian hillforts, at work ‘Radiocarbono y cronología de los castros asturianos’ (Cuesta Toribio et al. 1996). The criticisms received from some sectors of Asturian Archaeology (Camino Mayor 2000: 10, 12; Ríos González and García de Castro Valdés 2001: 95-97) forced to verify empirically the results obtained, reason why in 2001 new samples were collected and sent to UBAR for its dating, obtaining two new dates that came to ratify the previous ones (Jordá Pardo, Mestres Torres and García Martínez 2002).

Finally, during the study of the metallic materials carried out by Carlos Marín Suárez, a coal was found in a ferrous slag, which was dated in Beta Analytic Inc. (Miami, Florida, USA) obtaining a new date concordant again with the previous ones (Marín Suárez, Jordá Pardo and García-Guinea 2008: 56-59).

Therefore, at the moment there are eight radiocarbon dates that form a wide sequence ranging from the First Iron Age to the end of the hillfort Roman occupation (Jordá Pardo 2009; Jordá Pardo et al. 2009; Jordá Pardo, Marín Suárez and García-Guinea 2011) (Figure 1).

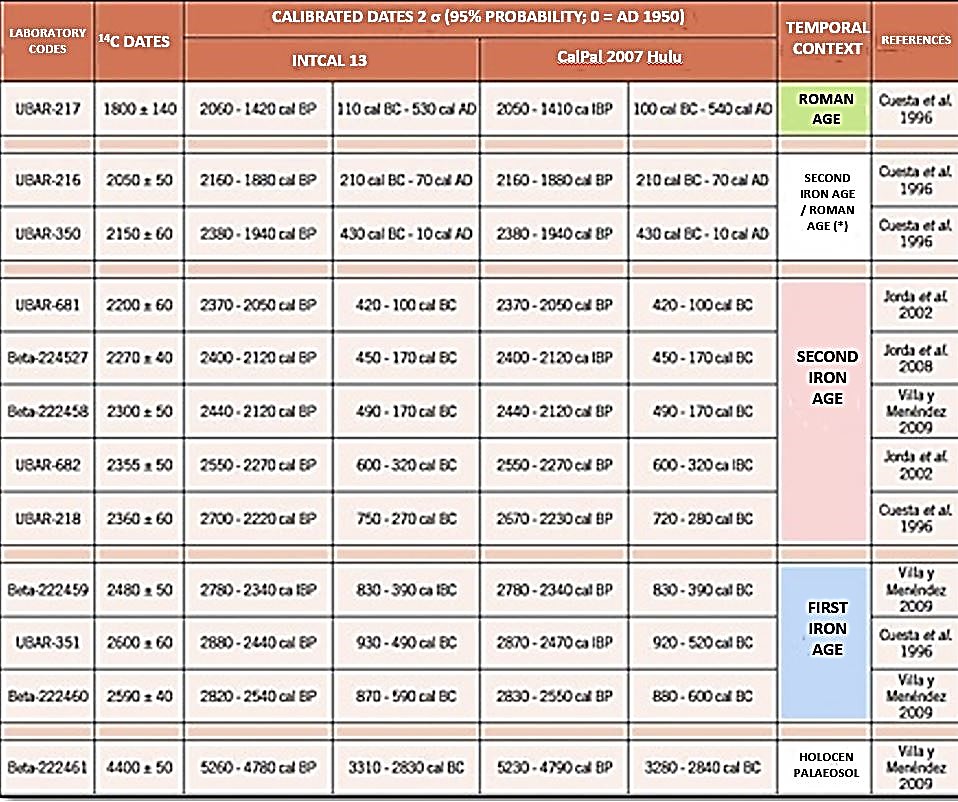

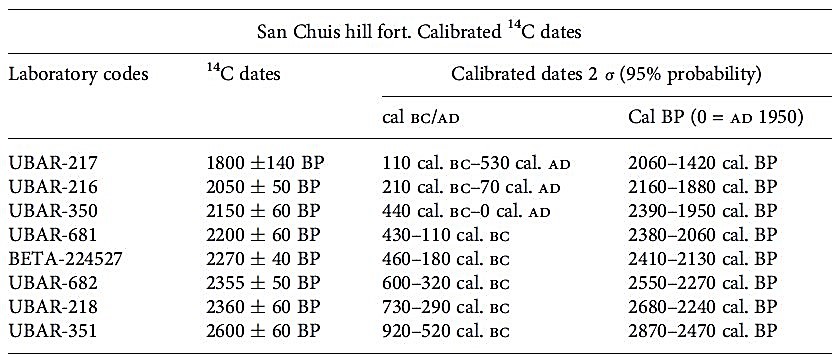

To perform the chronological analyses, the 14C date at 2 σ (95 per cent probability) were calibrated by the curve CalPal 2007 Hulu, included in the CalPal software (Version March 2007) (Weninger, Jöris, and Danzeglocke 2007). The calibration results are shown in Figures 2 and 3. Figure 2 displays the accumulated probability curves obtained from the calibration of the radiocarbon dates grouped by their chronostratigraphic position, showing its spatial and stratigraphic context and the related materials (Jordá Pardo, Marín Suárez and García-Guinea 2011: 492). Calibrated radiocarbon dates are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Calibrated radiocarbon dates. From Jordá Pardo, Marín Suárez and García-Guinea 2011: 493, Table 22.1 | Fechas radiocarbónicas calibradas. De Jordá Pardo, Marín Suárez y García-Guinea 2011: 493, Cuadro 22.1

Figure 3. Calibrated radiocarbon dates. From Jordá Pardo, Marín Suárez and García-Guinea 2011: 493, Table 22.1 | Fechas radiocarbónicas calibradas. De Jordá Pardo, Marín Suárez y García-Guinea 2011: 493, Cuadro 22.1PERIODS OF OCCUPATION

The oldest occupation period of the hillfort corresponds to the date UBAR-351 (A) 2600 ± 60 BP, whose calibration with the maximum probability (95%) offers a range of 920-520 cal. BC (Figure 84). This date was obtained from a sample collected in the Level VI b or UE-94 of the stratigraphic sequence obtained in the C-21 square, Structure 18, as we have seen previously in the epigraph 3.2.7.2. This level filled the paleotopography of the structure bottom and was positioned directly on the rock alteration of the substrate. The sample comes from a seed deposit located at the level’s base, within a small hole bounded by substrate rock and slate slabs, located at an approximate elevation of 778.50 m, about 55 cm below the walls’ start of the superimposed circular structure, as it appears in the planes made during the excavation. This level is associated with several post holes of a possible plant structure, which is stratigraphically below the foundations of the aforementioned circular stone structure and is partially affected by the construction works of the superimposed rectangular structure carried out by Romans. Pre-Roman pottery of the First Iron Age remains were found in it. Both the stratigraphy and the superposition of structures allow us to think that the basal level sampled corresponds to a stage of indigenous occupation of the village clearly prior to the generalized remodelling of the site of the Second Iron Age. The dated sample corresponds to the seeds found at this basal level, and they are a very valid element for dating the level that contains them since there is a minimum time span between the three processes involved in its genesis: collection, storage and combustion.

The next period of occupation of the hillfort is identified by six radiocarbon dates: UBAR-218 (D), BETA-224527 (H), UBAR-682 (C), UBAR-681 (B), UBAR-350 (G) and UBAR-216 (F). The first four meet perfectly the requirements of representativeness (association and synchrony) of the samples (Mestres Torres 2003), while the latter two meet the requirements of association, but lack synchrony, since the formation of the dated material is prior to the Archaeological event to which it is associated. Thus, in Figure 2, the two groups of dates are presented separately.

The date UBAR-218 (D) 2360 ± 60 BP (730 -290 cal. BC) corresponds to a sample of selected coals and carbonaceous earth with carbon remains that comes from the basal level arranged on the alteration of the slate substrate in the vicinity of the rampart of modules in the Low Quarter, inside the B-7 square (1985 campaign). This is the Level IV (SU-99), clayey by the decomposition of the parent rock, rich in charred organic matter, with domestic animal remains (cow, pig-boar). This area of the Lower Quarter (grids B-7, B-8, B-9, C-7 and C-8) corresponds to a space between the houses and the rampart, apparently empty, with small, slightly curved linear stone structures, which were positioned directly on the basal level of decomposed rock, and that were overlaid by some kind of paved road, presumably already of Roman time because it also covers nearby circular structures amortized at that time. Level IV (SU-99), interpreted as a garbage dump and underlying a level of Roman occupation (SU-97), leans on the inner facing of the rampartl of modules, hence the date UBAR 218 has been used as terminus post quem for the construction of the rampart (Cuesta Toribio et al. 1996: 231-232). This Level IV only contains pre-Roman pottery, which is in tune with its radiocarbon date and with the appearance of an eye bead at this level (Marín Suárez 2007), whose dating overlaps with UBAR 218 (4th-2nd centuries BC). Above it is a Roman level (Level III / SU-98) which has numerous fragments of Terra Sigillata Hispanica (TSH) and tegulae in relation to a large number of fragments of the pre-Roman pottery.

From this same area of the hillfort’s Low Quarter was obtained, in 2007, a new date for the top of Level IV: BETA-224527 (H) 2270 ± 40 BP (460 – 180 cal. BC). It was obtained from a sample of coal contained within a ferrous slag collected in the contact area between Level IV (UE-103) and Level III (EU-102), in square B-9 (1985 campaign) (Marín Suárez, Jordá Pardo and García-Guinea 2008; Jordá Pardo, Marín Suárez and García-Guinea 2011). This level is characterized by the presence of numerous slags and a multitude of ceramic remains, including some fragments of TSH, surpassed by the action of high temperatures in these squares. All this, together with the small arched structures that appear in the area, which can be interpreted as windbreaks, could be indicative of metallurgical work in this area, from pre-Roman times and possibly continuing into Roman times. It is quite likely that the removal of land, the result of said metallurgical work, altered the strata, mixing materials, which is why we would not find in B-9 any level exclusively with pre-Roman ceramics. However, in all these grids, both in the exclusively pre-Roman levels and in the Roman ones, there is a wide representation of pre-Roman ceramics. The interest of this date lies in the fact that for the first time the iron-making process is directly dated to times before the Roman occupation of the Asturian hillforts. This area has been considered as a work area or ‘artisan zone’.

Samples from which the dates UBAR 682 (C) 2355 ± 50 BP (600-320 cal. BC) and UBAR 681 (B) 2200 ± 60 BP (430-110 cal. BC) were obtained, were collected in a specific action in 2001. These samples come from the carbonaceous sediments attached to the inner facing of the foundations of the circular wall, located between the heights 779.10 and 779.05 m, between 30 and 25 cm below the Roman occupation floor of the structure 18 (square C-21) of the Upper Quarter (Jordá Pardo, Mestres Torres and García Martínez 2002). In view of the available data (Marín Suárez and Jordá Pardo 2007), the dated samples correspond to the upper section of Level VI inside the structure 18 or Level VI-a (SU-93), correlative to the petrification of this structure, and heavily affected by the works of Roman Age. That is the reason why it is only documented adhered to the circular walls, without any remain of it being found in the central area of the aforementioned structure. Among the few remains of this level, ceramics have not been recovered, although their attribution to the Second Iron Age seems clear both because of their stratigraphic position and because of the radiocarbon dates. According to the dates presented, Level VI-a of the interior of the Structure 18 (Upper Quarter) is clearly contemporary of Level IV of the ‘artisan zone’ next to the rampart (Lower Quarter).

As for the dates that present problems of association, the first one of them UBAR-350 (G) 2150 ± 60 BP (440 cal. BC – 0 cal. AD), was obtained of a fragment of coal collected in Level IV, concretely in the SU-89 of the stratigraphic sequence obtained in Structure 18 (Upper Quarter, C-21 square). This Level IV is located about 25/30 cm above Level VI-a from which UBAR-681 and UBAR-682 come, and corresponds to the Roman occupation floor of the rectangular structure that rests on the aforementioned old circular structure. The materials of this level correspond pre-Roman pottery, TSH and Roman common pottery, as well as fragments of iron, which situate it in the first moments of the Roman occupation of the hillfort, around the 1st century AD (Manzano Hernández 1985). At first glance, the date obtained for the sample of the level of Roman occupation does not appear to be in line with the expected one, with a minimum time lag between cultural dating and radiocarbon dating of about a century. We may be facing a fragment of wood charred during the development of the soil of Roman occupation, wood that had to be cut at a specific time of the calibrated range that offers the date by the pre-Roman inhabitants of the hillfort, and that could have been used as element of covering or support in the old circular structure, being resumed in Roman Age and subjected to combustion.

Something similar occurs with the date UBAR-216 (F) 2050 ± 50 BP (210 cal. BC-70 cal. AD). It comes from a sample of carbonaceous earth with abundant carbon remains collected in a level of carbonized organic matter (Level III, SU-77) that occupies the whole interior extension of the unique quadrangular structure in the vertex northeast of the Lower Quarter (Structure 6, D-5 square). It is a quadrangular structure of the Roman Age, for whose construction the destruction of three indigenous structures was necessary, being one under its foundations, filled by rubble, and the other two in close position. A slate slab pavement is placed at the foot of the quadrangular structure covering the outbreaks of the walls of another circular one. The radiocarbon date obtained corresponds to that of the plant materials used for the elaboration of the roofing of the quadrangular structure, inside of which they were collected. This vegetal roofing rose during the Roman occupation, probably in its beginnings when the destruction of certain structures for the construction of new ones took place. The roofing materials, according to their calibrated age, may correspond to remains of wood reused by the Romans from the indigenous constructions, or if we stick to the most recent date provided by the 2 sigma calibration they could even correspond to the early moments of Roman occupation. These roofing materials were subsequently burned down when Roman occupants left the hillfort, destroying the structure that supported them and rendering them useless for the purposes for which it was conceived.

Finally, the end of the Roman occupation of the hillfort was dated by UBAR-217 (E) 1800 ± 140 BP (110 cal. BC – 530 cal. AD), corresponding to a sample of carbonaceous earth with pieces of coal which comes from the vicinity of the rampart in the Lower Quarter (Square B-7). The sample was obtained at the base of a thin level (Level II) located above the general level of collapse of the village (Level III, SU-98), characterized by the presence of slabs and blocks of slate encompassed in a clayey- sandy matrix, product of the destruction of the masonry work of the structures’ walls. The sample was taken in the sequence that in the base contains the Level IV dated by UBAR-218, and stratigraphically is located above UBAR-216. The ceramic remains found in the sampled level correspond to a late occupation of the town, centred in the second century AD (Manzano Hernández 1985). This date represents the later hillfort’s occupation documented so far, which probably took place after its partial destruction. This agrees with the end of the west central Cantabrian hillforts that we can roughly place in the second century AD and the beginning of the third century AD.

COMPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

In 2006 and within the framework of the Archaeological Plan of Navia-Eo, Villa Valdés and Menéndez Granda undertake several surveys in the hillfort wall in order to know its stability and its solidity and to correct the possible pathologies that favoured the progress of cracks, loss of rigging and collapses (Villa Valdés and Menéndez Granda 2009). In order to confirm the stratigraphic series and to give chronology to the construction sequences recorded in the surveys, four organic samples were selected to estimate their age using radiocarbon (Figure 5).

The first sample (SC.01/06) was extracted from the sedimentary horizon originated at the foot of the modular wall in survey 3 and was identified by the laboratory as Beta-222458. The conventional date that it provided was 2300 ± 50 BP, which once calibrated to 2 sigma provided a double date range between 410-350 BC and 310-210 BC.

The second (SC.03/06), which also came from survey 3, was collected among the sediments accumulated against the outer facing of the primitive wall. Its laboratory ID is Beta-222459. It provided a conventional date of 2480 ± 50 BP which calibrated at 2 sigma offers a confidence interval between 790-410 BC.

The third sample (SC.04/06) proceeds from survey 1 and, as in the previous case, was collected among the accumulated deposits against the inner facing of the oldest wall, underlying the one of modular structure. Its laboratory ID is Beta-222460. It provided a conventional date of 2590 ± 40 BP that calibrated at 2 sigma offers a confidence interval between 820-770 BC.

The fourth and last sample (SC.05/06) also comes from survey 1. It was collected in the palaeosol on which the first of the walls would be installed. Its laboratory ID is Beta 222461. It provided a conventional date of 4.400 ± 50 BP which calibrated at 2 sigma offers a double date range between the 3320-3220 BC and 3120-2900 BC (Villa Valdés and Menéndez Granda 2009: 170-171).

The first and last sample have provided dates perfectly consistent with those obtained previously in San Chuis and come to confirm three fundamental facts already known:

- It can be considered practically proven that the San Chuis hillfort foundation takes place at the end of the Bronze Age, an issue that was already pointed out after the analysis of the first samples and the interpretation of the hillfort’s stratigraphic context.

- During the Second Iron Age, the ancient foundations experienced, as we have already noted in previous chapters, profound transformations in their urban and defensive structure. The walls of modules are one of the essential references in that perception of the change.

- The temporary framework in which the implantation of the modular walls is verified is essentially the same in all the Asturian western hillforts. Between the fourth century and the second century before Christ, its presence is confirmed in the Chao Samartín, in Cabo Blanco, in El Franco, and in Monte Castrelo de Pelóu, in Grandas de Salime.

However, the second and third samples (Beta-222459 and Beta-222460) have provided novel data. The first of them, Beta 222459, moves us to phase I-c, that transitions with the Second Iron Age, with dates 790-410 B C. It might lead us to think that after the foundation of a fortified settlement in the I-b phase mainly circumscribed to the Upper Quarter, an expansion of the space constructed would have taken place in this phase of transition or I-c. These new dimensions would finally stabilize at the beginning of phase II with the construction of the wall of modules. However, the second dating (Beta-222460 with dates 820-770 BC) leads us to reconsider this chronology as well as the hillfort’s urban evolution, since, according to its calibration, it seems that this first continuous wall was raised in the same moment of the hillfort’s foundation. It may be suggested then that this north-eastern corner of the village or Lower Quarter, could have been occupied, like the Upper Quarter, from the first moment of its foundation, in phase I-b, and that was defended with a continuous wall of about 1.5 m wide. From this phase of the First Iron Age we count with the Structure 18 of the Upper Quarter and with these sections of continuous wall of the Lower Quarter (Jordá Pardo, Marín Suárez and Molina Salido 2014: 155).

Below, in Figure 7, we can see a summary table with all the existing data of San Chuis and its bibliographic references:

REFERENCIAS

REFERENCES

Camino Mayor, J. (2000). Las murallas compartimentadas en los castros de Asturias: bases para un debate. AEspA, 73: 27-42.

Cuesta Toribio, F., Maya González, J. L., Mestres i Torres, J. S. y Jordá Pardo, J. F. (1996). Radiocarbono y cronología de los castros asturianos. Zephyrus: Revista de prehistoria y arqueología, 49: 225-270.

Jordá Cerdá, F. (1984). Notas sobre la cultura castreña del noroeste peninsular. Memorias de Historia Antigua, VI: 7-14.

Jordá Cerdá, F. (1985). Allande: castro de San Chuis. Arqueología 83: 80.

Jordá Pardo, J. F. (2009). Descubriendo el castro de San Chuis (Allande, Asturias): nuevas aportaciones al conocimiento de la cronología radiocarbónica de los castros asturianos. ENTEMU, XVI: 47-63.

Jordá Pardo, J. F., Mestres Torres, J. S. y García Martínez, M. (2002). Arqueología castreña y método científico: nuevas dataciones radiocarbónicas del Castro de San Chuis (Allande, Asturias). Croa, 12: 17-36.

Jordá Pardo, J. F. et. al. (2009). Radiocarbon and Chronology of the Iron Age Hillforts. En J. Karl, & R. Leskovar (Edits.), Interpretierte Eisenzeiten. Fallstudien, Methoden, Theorie. Tagungsbeiträge der 3 Linzer Gespräche

zur interpretativen Eisenzeitarchäologie, Studien zur Kulturgeschichte von Oberösterreich 22: 81-98). Linz: Oberösterreichischen Landesmuseum.

Jordá Pardo, J. F., Marín Suárez, C. y García-Guinea, J. (2011). Discovering San Chuis Hillfort (Northern Spain): Archaeometry, Craft Technologies and Social Interpretation. En T. Moore y X. L. Armada (Edits.), Atlantic Europe in the First Millennium BC. Crossing the Divide: 488-505. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jordá Pardo, J. F., Marín Suárez, C. y Molina Salido, J. (2014). El castro de San Chuis (San Martín de Beduledo, Allande, Asturias): cincuenta y dos años de investigación arqueológica. Anejos de Nailos. Estudios

Interdisciplinares de Arqueología. Francisco Jordá Cerdá (1914-2004) Maestro de Prehistoriadores, 2: 135-175.

Manzano Hernández, M. P. (1986-87). Avance sobre la cerámica común del castro de San Chuis. Pola de Allande. Zephyrus, 39-40: 397-410.

Marín Suárez, C. (2007). Los materiales del castro de San L.luis (Allande, Asturias). Complutum, 18: 131-160.

Marín Suárez, C., Jordá Pardo, J. F. y García-Guinea, J. (2008). Arqueometría en el castro de San Chuis (Allande, Asturias, España). En E. Ramil Rego (Ed.), I Congreso Internacional de Arqueoloxía de Vilalba: 53-62.

Férvedes, número monográfico.

Mestres Torres, J. (2003). La química i la cronologia: la datació per radiocarboni. Revista de la Societat Catalana de Quiímica, 4: 10-25.

Molina Salido, J (2018). From the Archaeological Record to Virtual Reconstruction The Application of Information Technologies at an Iron Age Fortified Settlement (San Chuis Hillfort, Allande, Asturias, Spain), Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.

Ríos González, S. y García de Castro Valdés, C. (2001). Observaciones en torno al poblamiento castreño de la Edad del Hierro en Asturias (1). Trabajos de prehistoria, 58 (2): 89-107.

Villa Valdés, A. y Menéndez Granda, A. (2009). Estudio cronoestratigráfico de las murallas del castro de San Chuis en San Martín de Beduledo (Allande, Asturias). Boletín de Letras del Real Instituto de Estudiuos Asturianos, 173-174: 159-179.

Funciona gracias a WordPress

CASTRO DE SAN CHUIS © 2024 by JUANA MOLINA SALIDO is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International