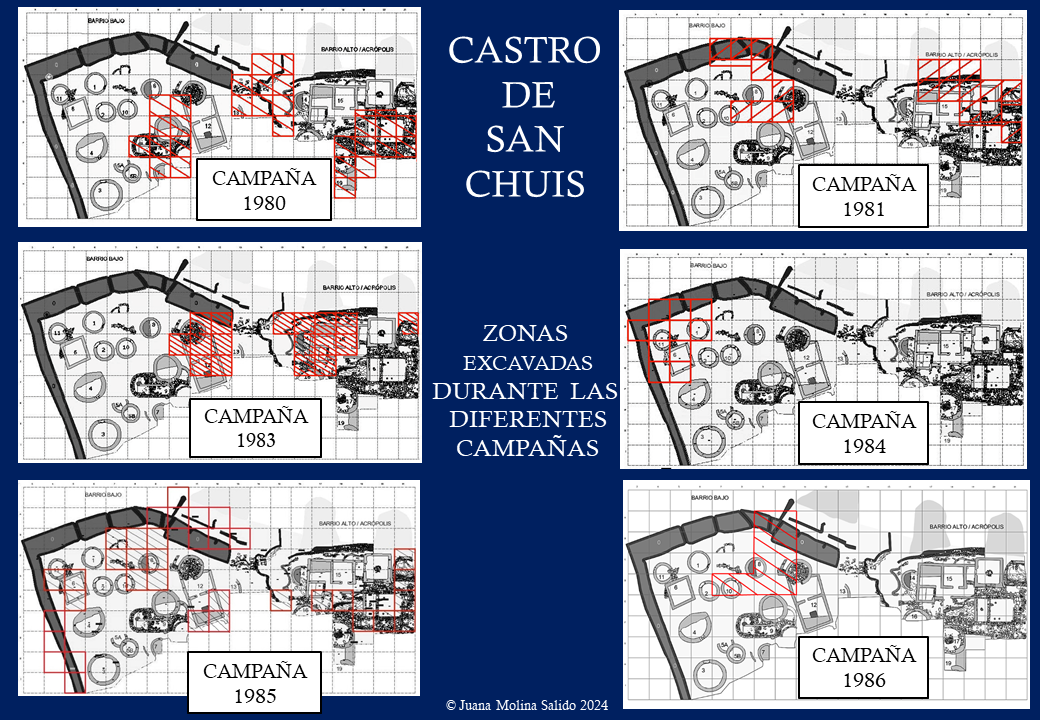

Zonas excavadas durante las diferentes campañas

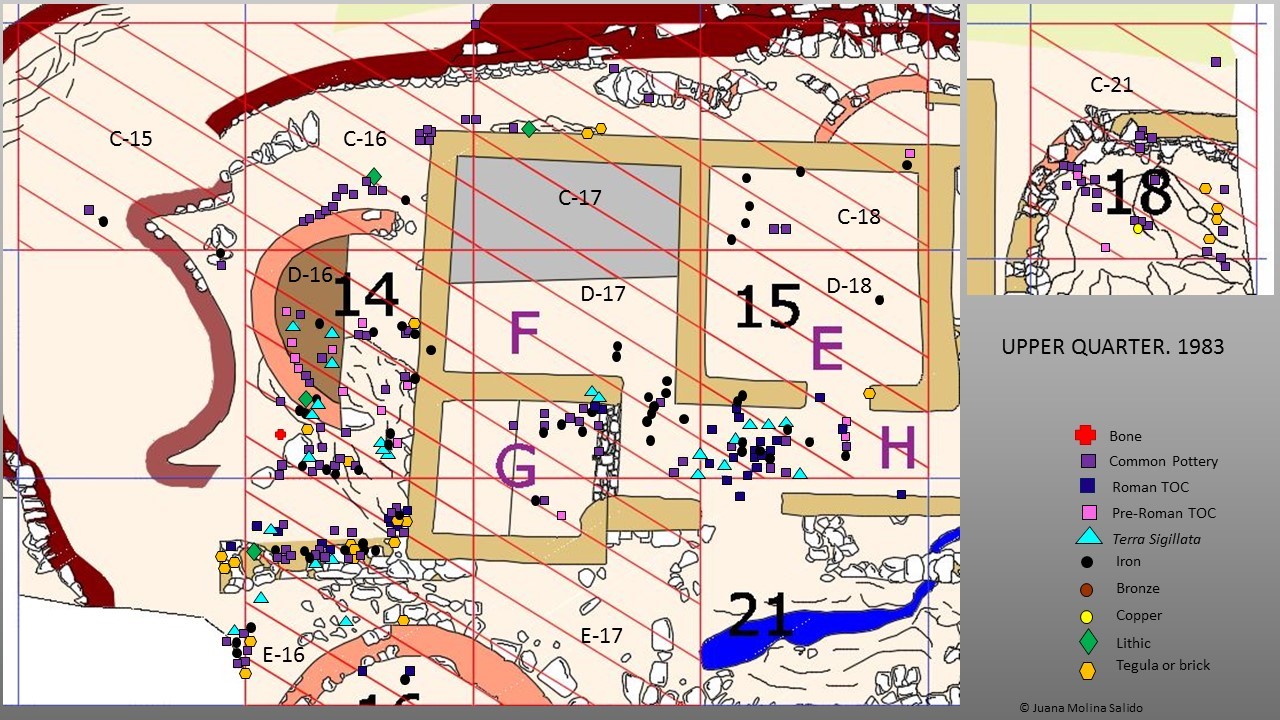

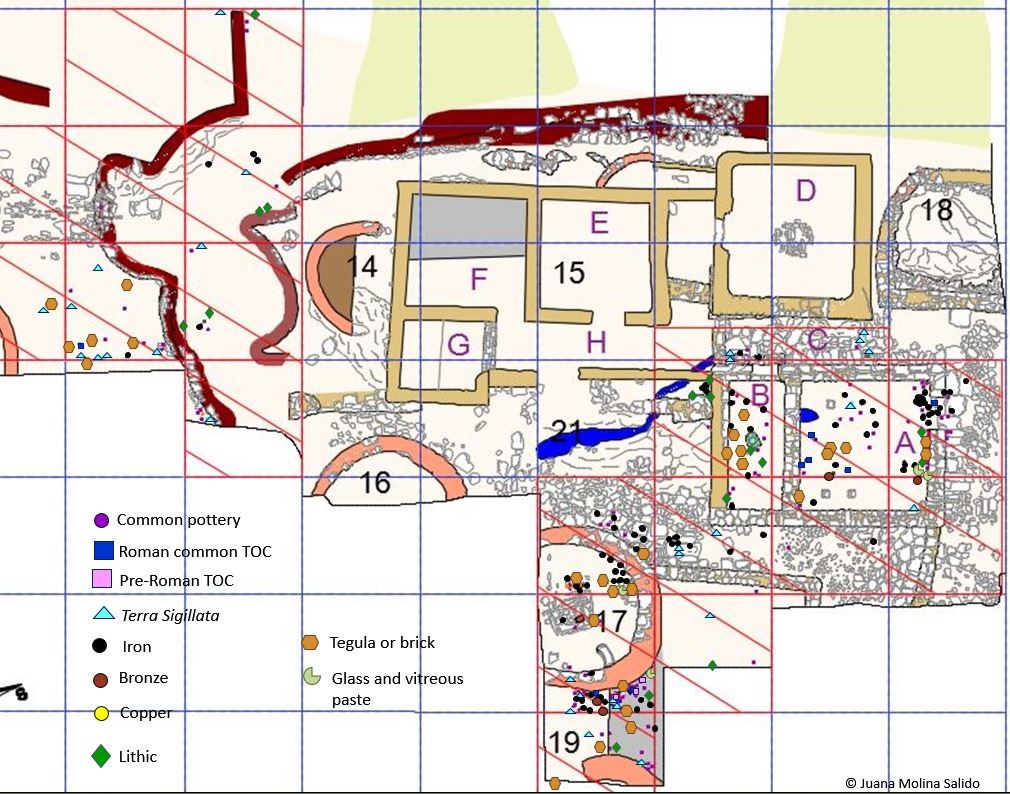

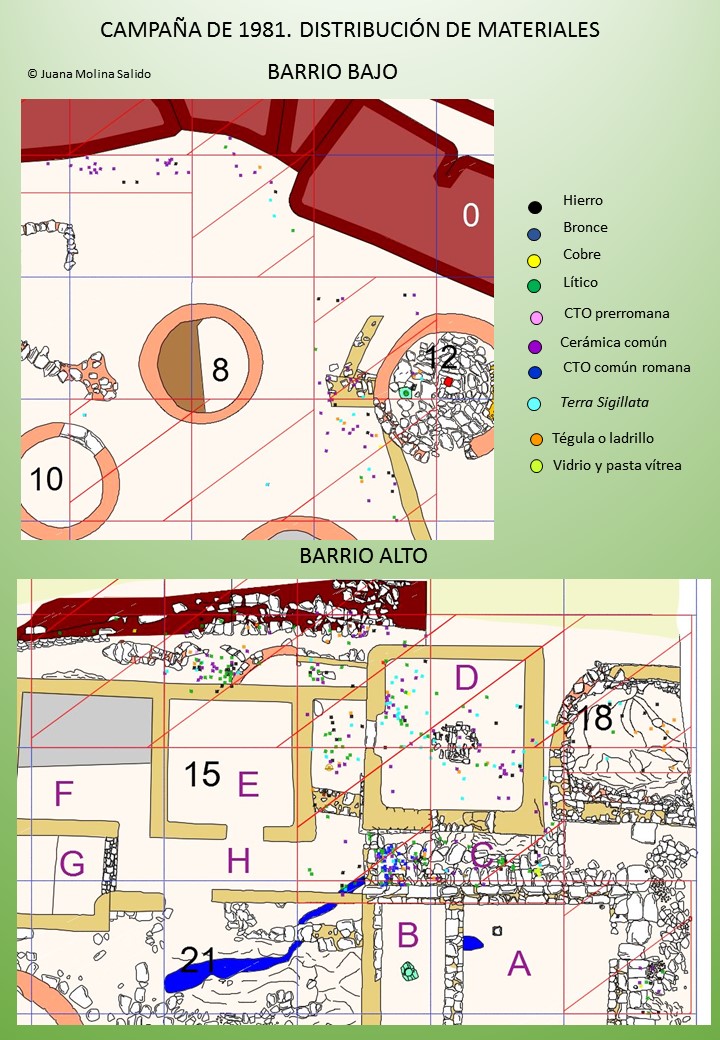

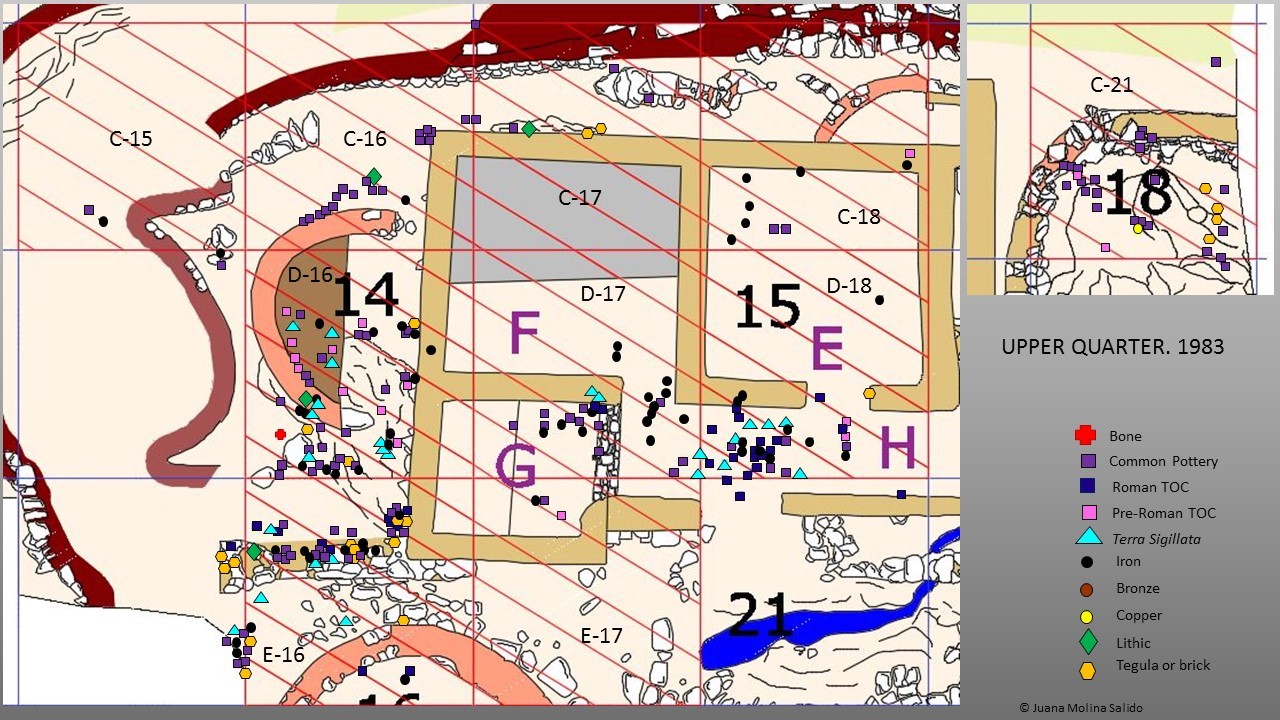

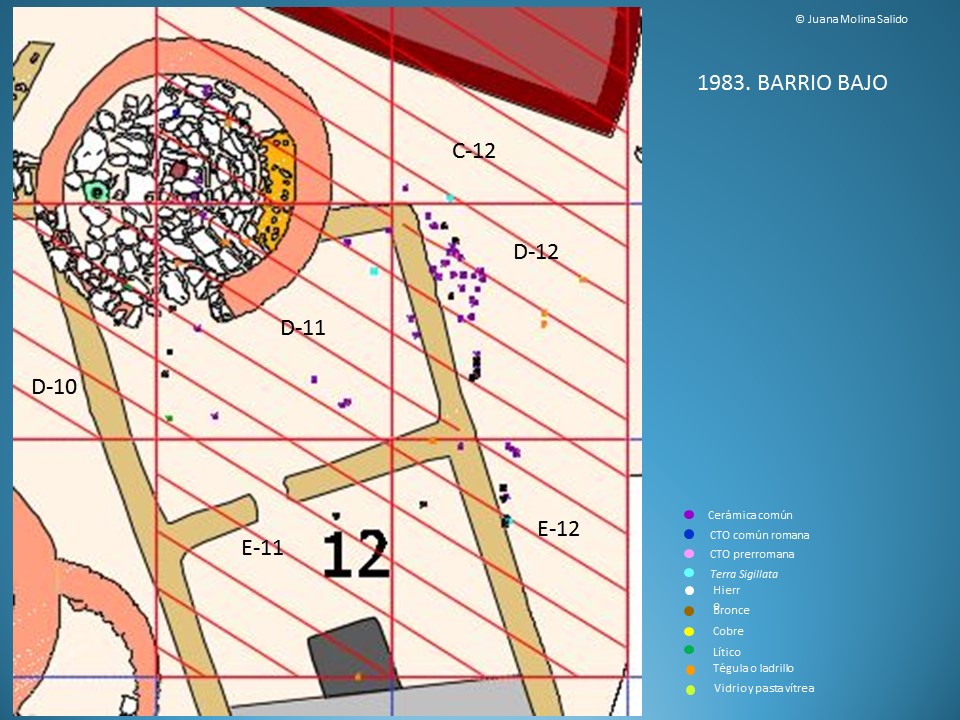

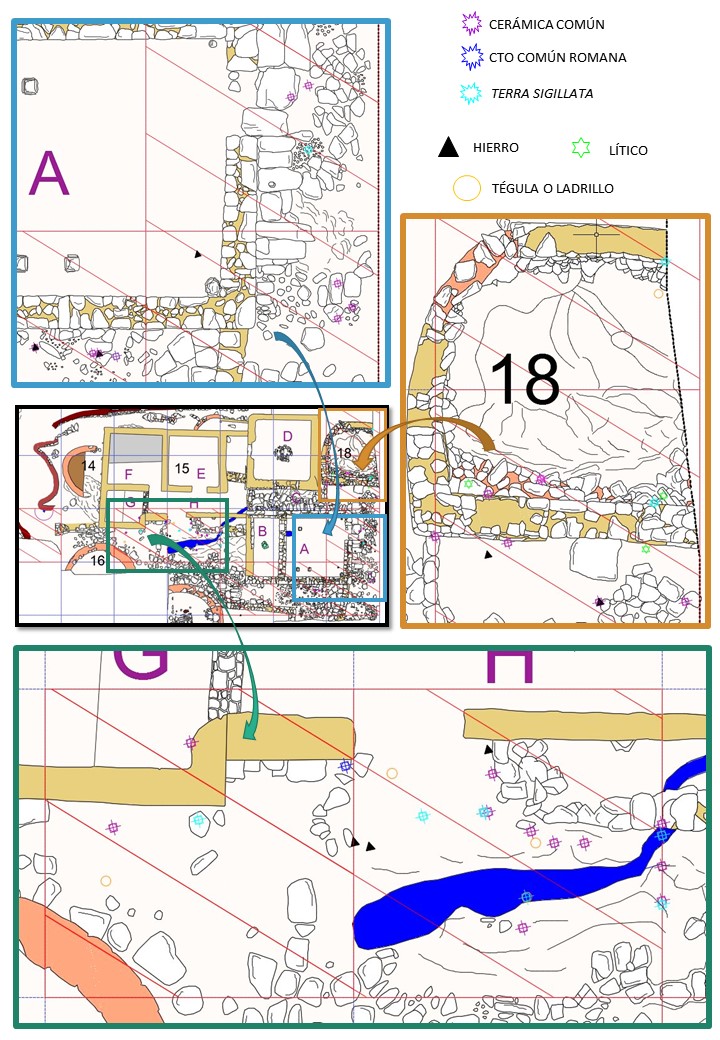

Distribución del registro durante las diferentes campañas | Record distribution during the different campaigns

ANÁLISIS ESPACIAL

El análisis del contexto y de las relaciones de los diferentes elementos del registro material nos va a permitir estudiar el castro desde otras perspectivas. En general, los análisis espaciales permiten deducir las diferentes funcionalidades de cada área de los yacimientos. También nos permiten establecer qué estructuras están relacionadas entre sí, formando lo que se conoce como unidades de ocupación. Normalmente una unidad de ocupación se compone de varias estructuras y del espacio que existe entre ellas, aunque pueden existir

unidades compuestas de una sola estructura. El espacio que existe entre estas estructuras es donde se suelen llevar a cabo las labores cotidianas necesarias para el mantenimiento de una familia y es donde suelen aparecer los molinos circulares y otras herramientas propias del trabajo, en este caso y momento, femenino.

Fue durante la Segunda Edad del Hierro cuando se inició este fenómeno social en la zona. La Segunda Edad del Hierro está marcada por la tensión entre la tradicional identidad comunal, o de poblado, y la familiar. Un fiel reflejo de esta tensión y que es uno de los rasgos arquitectónicos del extremo occidental cantábrico, tanto en la costa (Coaña, Mohías) como en el interior (San Chuis), es que se comienzan a establecer como privados ciertos espacios que con anterioridad eran de uso semipúblico, pasando a ser de uso exclusivo de una sola familia conformando unidades de ocupación que reúnen varias estructuras y su espacio intermedio (Marín Suárez 2007: 152-157; Marín Suárez 2011a: 444-446).

Es importante señalar que si solo hacemos referencia a las unidades de la Fase II, el barrio alto debería quedar al margen puesto que fue totalmente reformado en época romana. Sin embargo, podemos hacer extensivo el sistema de unidades a esta parte del castro teniendo presente que estas se conformarían en la fase III y no en la II.

Por lo tanto, teniendo en cuenta todo esto, la forma y disposición de las estructuras de San Chuis y la dispersión de los elementos del registro, hemos podido reconocer las unidades de ocupación que hemos señalado en la imagen (Figura 1).

Hemos considerado tanto el hecho de que aparezcan ciertos materiales líticos (molinos o fusayolas), como el que las viviendas enfrenten su puertas entre si facilitando la visibilidad y la circulación entre las mismas.

En este sentido las estructuras 3, 4 y 5A-B podrían considerarse una unidad de ocupación (UO-1) compuesta por una estructura con hogar (3) y una aparentemente sin hogar y con banco corrido (4) que tienen sus puertas de entrada enfrentadas. Esta unidad fue muy bien estudiada por Marín Suárez en 2007 cuando analizó los materiales de las primeras campañas del castro, 1962 y 1963 (Marín Suárez 2007).

El molino circular corroboraría un lugar de trabajo femenino en el patio ubicado entre ambas (Figura 195). Junto a ellas la estructura 5B que debe interpretarse como la base de un posible granero tipo cabazo, como también parece indicarlo la alta concentración de contenedores cerámicos de esta zona. El muro curvo 5A se interpreta como una zona de trabajo, quizás artesanal, que podría estar representado por la fusayola, aneja a este granero. Desconocemos qué posible función pudieron tener los dos alineamientos de grandes piedras sin trabajar de la parte occidental de 5B.

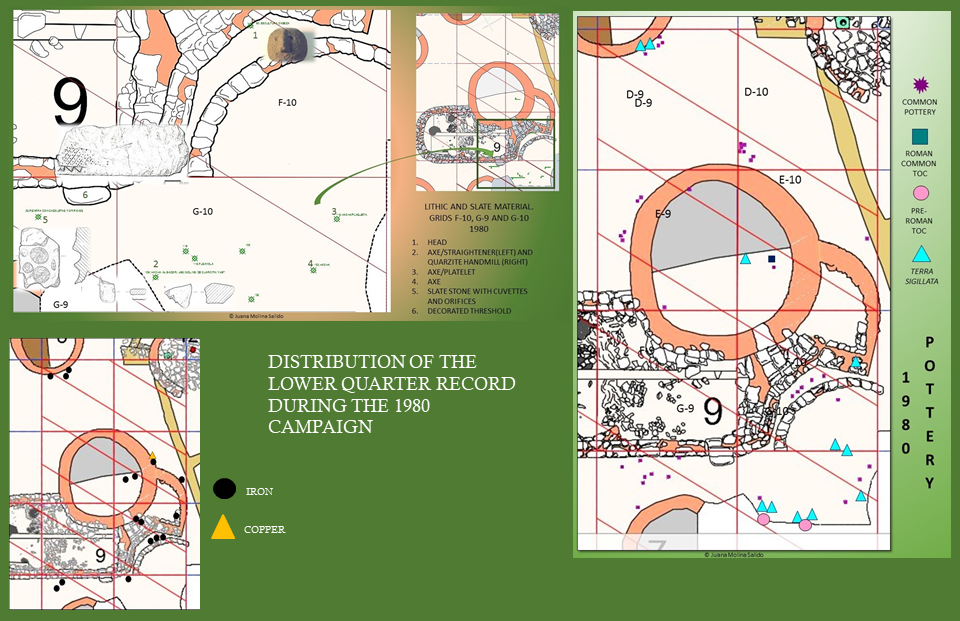

Las estructuras 2 y 11 y las amortizadas por 6 pudieron haber constituido otra unidad de ocupación (UO-2). En cualquier caso ahora es muy difícil establecerlo con seguridad puesto que la Estructura 6 cambiaría completamente tanto la fisionomía de la zona como su uso: podría ser una torre de vigilancia o como ya hemos comentado un posible almacén, granero u hórreo o cabazo. En cualquier caso aparece un molino en el interior de la estructura cuadrangular. Por lo que se refiere a la UO-3 formada por la Estructura 9, de la que ya hemos hablado, la unidad de ocupación se integra uniendo dos casas con el muro. Así, lo que se hizo en este caso fue privatizar con muros un espacio que en el resto de unidades de ocupación era semipúblico. Además se pone un umbral decorado y es precisamente en esta estructura donde aparece una de las pocas esculturas de cabeza cortada de esta zona occidental cantábrica. Además, como nos demuestra la distribución del material lítico, existe una concentración de dicho material frente al acceso de la unidad que la diferencia aún más del resto de unidades del barrio bajo.

Las grandes cabañas comunales de la fase I y los rituales guerreros que se le asocian en el vecino valle del Navia nos están revelando unas prácticas sociales caracterizadas por el etos igualitario y por el sentido de comunidad aldeana, pero en donde está apareciendo con fuerza un nuevo etos guerrero, materializado en esos rituales y en las propias defensas de los poblados, que comienza a romper la isonomía heredada de la Edad del Bronce. El paso a la Segunda Edad del Hierro (Fase II) supuso el comienzo del fin del igualitarismo dentro de cada poblado. Las murallas monumentales que ahora delimitan a los castros seguramente debieron seguir ratificando cotidianamente el sentido de comunidad aldeana, pero esta comunidad ahora cuenta con mayor número de miembros –en la Fase II se amplían la mayoría de los castros y se fundan muchos castros de nueva planta– y además aquella se distribuye en unidades de ocupación claramente definidas y entre las que empieza a ver diferencias formales y de tamaño, así como privatizaciones de espacios (Marín Suárez 2011a: 442-449).

No nos hemos atrevido a llamar unidad de ocupación a la Estructura 12. Es también la suma de dos estructuras, una indígena circular y otra ya romana que se une a esta en lo que fue su antigua entrada, pero su funcionalidad se desconoce. Mencionar que la estructura circular, además de tener el suelo enlosado y el hogar central, presenta una especie de repisa de sillarejo de pizarra adosada al muro, un banco semicircular sobre el enlosado entre el hogar y la repisa de sillarejo y una piedra de cazoleta enterrada a ras del enlosado en el N de la citada habitación. No es la única: aparece otra dentro de la estructura rectangular y fuera de ella, junto al muro norte, otra, si bien ambas de menor tamaño. Desconocemos la zona de acceso posterior a la unión de ambas estructuras, probablemente el acceso estuviera en altura, en la fachada sur por medio de una escalera en material perecedero. Seguramente tendría un uso ritual o religioso, con una zona interior donde se sitúa el hogar como centro neurálgico. Los materiales encontrados no nos han proporcionado más indicios al respecto. Aparecen fragmentos de TSH pero muy deteriorados, de CTO común romana muy fragmentados y algunos de hierro sobre todo fragmentos de clavos.

Una zona bien excavada y aparentemente con una funcionalidad muy concreta es la que hemos señalado como zona industrial en su sentido productivo o artesanal, un lugar en el que se transforma o se obtiene un producto. La distribución y la composición del registro material nos llevan a pensar en que fuese una zona multiusos: de despiece de ganado bovino, de fundición en un momento determinado, incluso basurero dada la alta concentración de restos cerámicos existentes. Por otro lado, puede que también se llevaran a cabo otras actividades complementarias, puesto que también aparecen molinos y fusayolas. Probablemente una unidad familiar o varias residiesen en las habitaciones que se incluyen en la zona y por esto aparecen los instrumentos propios del trabajo femenino unidos a los demás. Es cierto que aparece material de hierro en esta zona y que los restos de las cuadrículas B-7 y B-8 son en buena parte escoria (7 fragmentos de escoria, frente a 7 registros de clavos muy fragmentados), pero no sabemos hasta qué punto esto nos permite decir que es una zona metalúrgica en exclusiva, o solo metalúrgica. Probablemente lo era todo a la vez. Al oeste de la estructura 8 que nosotros hemos incluido como parte de esta zona productiva, en la cuadrícula D-9, existe también una alta concentración de restos de piezas de hierro entre los que se incluyen muchos clavos, piezas de guarnicionería, placas de hierro algunas con restos de remaches, una varilla, es decir una buena parte de los restos de hierro que se restauraron. Esto nos ha hecho añadir esta habitación y su área circundante también en esta zona industrial. Destacar también la altísima densidad de restos cerámicos que existen en esta zona, sobre todo en las cuadrícula B-7 y C-7, que como hemos dicho nos hace pensar que también fuese un basurero. En definitiva, ha sido una zona muy utilizada.

Las unidades 4 y 5 que hemos señalado en el barrio alto evidentemente corresponden ya a una sociedad con una organización muy compleja, la romana, que no tiene nada que ver con la sociedad indígena a la que domina. Esta estructura, como ya dijimos, sigue el modelo militar tipo contubernium. En cuanto a las dos pequeñas unidades que permanecen al lado de estas, una de ellas, la Estructura 18 tiene un suelo de ocupación romano por lo que tuvo una ocupación romana ligada a la calle o corredor C antes de que lo tabicaran. Recordar que esta estructura fue de las primeras en construirse en el castro: comenzó su larga andadura en la primera Edad del Hierro con una estructura vegetal y huellas de poste, posteriormente durante la Segunda Edad del Hierro es petrificada si bien mantiene su forma circular y por último en la fase romana es rectangularizada. En cuanto al Estructura 17, suponemos que continuó siendo una vivienda indígena aunque desconocemos si tenía relación con alguna más puesto que su territorio circundante está sin excavar.

REFERENCIAS

Marín Suárez, C. y Jordá Pardo, J. F. (2007). Las cerámicas indígenas del castro de San Lluis (Allande, Asturias). En A. Fanjul Peraza (Ed.), Estudios varios de Arqueología castreña. A propósito de las excavaciones en los castros

de Teverga (Asturias): 135-152. Santander: I.E.P.A.

Marín Suárez, C. (2011). De nómadas a castreños: el primer milenio antes de la era en el sector centro-occidental de la Cordillera Cantábrica. Madrid: Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Molina Salido, J (2018). From the Archaeological Record to Virtual Reconstruction The Application of Information Technologies at an Iron Age Fortified Settlement (San Chuis Hillfort, Allande, Asturias, Spain), Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd

SPATIAL ANALYSIS

The analysis of the context and the relations between the different elements of the material record will allow us to study the hillfort from other perspectives. In general, the spatial analysis allows to deduce the different functionalities of each site area. It also allows us to establish which structures are related to each other, forming what are known as occupation units. Usually an occupation unit consists of several structures and the space that exists between them, although there may be units composed of a single structure. The space existing between these structures is where the daily tasks necessary for the family maintenance were usually carried out and it is where usually the circular mills and other work tools, in this case and moment, feminine, appear.

It was during the Second Iron Age when this social phenomenon began in the area. The Second Iron Age is marked by the tension between the traditional communal identity, or village identity, and the familiar identity. A faithful reflection of this tension, that is one of the architectural features of the west Cantabrian extreme, both on the coast (Coaña, Mohías) and in the interior (San Chuis), is that they begin to establish certain spaces that previously were of semi-public use as private, becoming an exclusive use area for a single family, forming occupation units that bring together several structures and their intermediate space (Marín Suárez 2007: 152-157; Marín Suárez 2011a: 444-446).

It is important to note that if we only refer to the units of Phase II, the Upper Quartet should remain on the sidelines since it was completely renovated in Roman times. However, we can extend the system of units to this hillfort zone bearing in mind that these would be conformed in Phase III and not in II. Therefore, taking into account all this, the shape and layout of the San Chuis structures and the dispersion of the record’s elements that we have seen, we have been able to recognize the occupation units that we have indicated in the image (Figure 1).

We have considered both the fact that certain lithic materials (mills or fusayolas) appeared, and that the houses doors were facing each other, facilitating the visibility and circulation between them.

In this sense, the Structures 3, 4 and 5A-B could be considered an occupation unit (OU-1) composed of a structure with a fireplace (3) and another apparently without fireplace but with a bench (4). The doors of both structures were facing each other. This unit was very well studied by Marín Suárez in 2007 when he analysed the materials of the hillfort first campaigns, 1962 and 1963 (Marín Suárez 2007).

The circular mill would corroborate a female work place in the space/yard between them. Next to them is the structure 5B that must be interpreted as the base of a possible granary type Asturian cabazo,[1] as it also seems to indicate the high concentration of ceramic containers in this zone. The curved wall 5A was interpreted as a work zone, perhaps artisan, which could be represented by the fusayola, attached to this barn. We do not know what possible function the two alignments of large unworked stones located at the western part of 5B could have.

Structures 2 and 11 and those demolished to build Structure 6 could have constituted another occupation unit (OU-2). In any case now it is very difficult to establish it for sure since Structure 6 would completely change both the physiognomy of the area and its use: it could be a watch tower or as we have already mentioned a possible warehouse, barn or hórreo. Either way, a mill appears inside the quadrangular structure.

Regarding the OU-3 formed by Structure 9, of which we have already spoken, the occupation unit is integrated joining two houses by means of the wall. Thus, in this case, what was done was to privatize with walls a space that in the rest of occupation units was semi-public. In addition, a decorated threshold was placed on the entrance door, and it is precisely in this structure in which one of the few cut head sculptures of this western area of the Cantabrian region has been found. Also, as the distribution of the lithic remains shows, there is a concentration of this material type in the zone next to the unit access door (Figure 167) that makes it even more different from the rest of the units in the Lower Quarter.

This occupation unit would be an example of the architecture differential evolution that must be related to the increase of power and / or accumulation of wealth of any nature whatsoever, of this family group with respect to the rest of the community that inhabited the hillfort, which would lead them to exhibit the family identity through the architectural reforms mentioned and with the decoration of the door of this complex structure, since it is the house part with greater symbolism. This is coherent with the idea that the small communities which inhabited the hillforts began in the fourth century cal. BC to have a clear internal division into family units, among which inequalities that will gradually become more defined began to develop (Parcero Oubiña et al. 2007: 216; Marín Suárez 2011a: 442-449).

It is interesting to note that the large communal huts of Phase I and the warrior rituals associated with them in the neighbouring Navia Valley are revealing to us social practices characterized by the egalitarian ethos and the sense of village community, but in where a new warrior ethos is appearing with force, embodied in these rituals and own village defences, which begins to break the isonomy inherited from the Bronze Age. The passage to the Second Iron Age (Phase II) was the beginning of the end of egalitarianism within each village. The monumental walls that now delimit the hillforts probably had to continue ratifying daily the sense of village community. But nevertheless, this community now has a larger number of members – in Phase II most of the hillforts are expanded and many new hillforts are founded – and, in addition, it is distributed in clearly defined occupation units among which formal and size differences begin to be seen, as well as privatizations of spaces (Marín Suárez 2011a: 442-449).

We have not dared to call occupation unit to Structure 12. It is also the sum of two structures, an indigenous circular one and another Roman joined to it by what in the past was its former entrance, but its functionality is unknown. The circular structure, in addition to having the floor paved and a central fireplace, presents a kind of slate ashlar shelve attached to the wall, a semicircular bench on the pavement between the fireplace and the ashlar shelve, and a stone with cuvette buried at ground level in the north of the mentioned room. It is not the only one: another appears inside the rectangular structure, and outside of it, next to the north wall, another, although both smaller. We do not know the access zone after the union of both structures, probably the access was in height, in the south façade by means of a perishable material staircase. It would surely have a ritual or religious use, with an interior zone where the fireplace is located as a nerve centre. The materials found have not provided us with any further evidence. Fragments of very deteriorated Terra Sigillata Hispanica appear, in addition to some remains of common Roman TOC very fragmented and some of iron, mainly fragments of nails.

A well excavated area and apparently with a very specific functionality is what we have identified as an ‘industrial’ zone in its productive or artisanal sense, a place where a product is transformed or obtained. The distribution and composition of the material record leads us to think that it was a multipurpose area: of bovine cattle cutting, of smelting at a given time, even dump because of the high concentration of pottery remains existing. On the other hand, other complementary activities may have also been carried out, since there are also mills and fusayolas. Probably a family unit or several resided in the rooms that are included in the area and due to this the feminine work tools together with the others appear. It is true that iron material appears in this area and that the remains of grids B-7 and B-8 are largely slag (7 slag fragments, versus 7 very fragmented nail records), but we do not know if this allows us to say that it is an exclusive metallurgical zone, or only metallurgical zone. It probably was everything at once. We have not been able to establish whether the use as smelting or cutting area is related to the temporal sequence, i.e. if during each period it had a different function. All the bone and iron remains appeared in Levels III and IV indistinctly, and also those of pottery, although pottery has continuity also in the Level II, not being any special concentration of one kind of remain in particular. Therefore, it seems that the use was simultaneous rather than sequential. To the west of the Structure 8, that we have included as part of this productive zone, in the grid D-9, there is also a high concentration of remains of iron pieces including many nails, saddlery, iron plates, some with remains of rivets, a rod, that is to say, a good part of the rest of iron that were restored. This has made us add this room and its surrounding area also in this ‘industrial’ area. In short, it has been a very used area.

The units 4 and 5 that we have indicated in the Upper Quarter obviously correspond to a society with a very complex organization, the Roman, which has nothing to do with the indigenous society that it dominates. This structure, as we have already mentioned, follows the military model type contubernium. As for the two small units that remain next to this, one of them, Structure 18 has a Roman occupation ground, so it had a Roman occupation attached to the street or corridor C before it was partitioned. We want to remember that this Structure was one of the first to be built in the hillfort. It began its long history in the first Iron Age with a vegetal structure of which post footprints were conserved. Later during the Second Iron Age, its walls were petrified, although it maintains its circular shape. Finally, in the Roman phase, it was refurbished and built with a rectangular shape. Regarding Structure 17, we assume that it remained an indigenous dwelling although we do not know if it was related to any other since its surrounding territory is not excavated.

[1] Small granary of circular form and raised upper the ground whose upper part is made with perishable materials